I. Introduction

“We therefore hold that the Constitution does not confer a right to abortion. Roe and Casey must be overruled, and the authority to regulate abortion must be returned to the people and their elected representatives.”[1] These are the words that Justice Samuel Alito announced in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization,[2] which sent the states into a tailspin. Laws dating back to the 1800s returned from their grave,[3] states began to pass laws which restricted healthcare for millions of individuals,[4] and children have been forced to carry pregnancies to term which were the result of rape.[5]

Advocates for the right to choose turned their attention to the states. State supreme courts became a hotbed for state constitutional protections for abortion. These courts often relied on federal protection to justify state constitutional protection, and now they were faced with whether their own constitution independently protects abortion. Iowa was no different. On June 16, 2023, the Iowa Supreme Court was split 3–3 in a case where the Court had the opportunity to reinforce or tear down constitutional protections for abortion.[6] However, because of a complicated procedural history and the operation of law, abortion remains protected in the State of Iowa, for now.

II. Background

In 2018, the Iowa Legislature passed Iowa Code chapter 146C, colloquially known as the “fetal heartbeat bill.”[7] This law prohibited physicians from performing abortions whenever an ultrasound detected a fetal heartbeat.[8] There were few exceptions which allowed the physician to move forward with the procedure, including if a medical emergency existed, if the abortion was medically necessary, if the pregnancy was the result of rape or incest, if the treatment was required for an incomplete miscarriage, or there were fetal abnormalities.[9] At the time the fetal heartbeat bill was passed, the controlling Iowa law had not yet determined whether the Iowa Constitution guaranteed protections for abortion. However, Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey still guaranteed the right to an abortion at the federal level. Nonetheless, Planned Parenthood filed suit just two weeks after the law passed requesting declaratory judgment and injunctive relief.[10] The parties stipulated to a temporary injunction in June 2018, and eventually the State moved to dismiss the case since the Iowa Supreme Court in its most recent abortion case sidestepped the question about whether the state constitution protected a right to abortion.[11] Although there was a gap in the law, it was settled Iowa law that the abortion regulations were subject to the undue burden standard, a special form of intermediate scrutiny.[12]

In the summer of 2018, shortly after the temporary injunction was put in place, Planned Parenthood of the Heartland v. Reynolds ex rel. State, 915 N.W.2d 206 (Iowa 2018) (hereinafter PPH 2018), held that abortion was a fundamental right protected by the Iowa Constitution.[13] This therefore increased the level of scrutiny applied to regulations on abortion, raising it from the undue burden standard to strict scrutiny.[14] The State withdrew its motion to dismiss and Planned Parenthood filed a motion for summary judgment.[15] In 2019, the district court granted the motion and permanently enjoined the State from implementing and enforcing the fetal heartbeat law.[16]

Many thought that this would be the end of the story and the right to choose would become an engrained Iowa constitutional principle.[17] Unfortunately, just four years later, in Planned Parenthood of the Heartland, Inc. v. Reynolds ex rel. State (hereinafter PPH 2022), the Iowa Supreme Court overruled PPH 2018 to the extent that the Iowa Constitution viewed the right to abortion as a fundamental right and thus subject to strict scrutiny.[18] The Court remained split on what the applicable standard should be in reviewing regulations for abortion. Three justices believed that the Court should wait to receive more guidance from the United States Supreme Court and need not answer the question in this specific case. The three-justice plurality believed that this kept PPH 2015 as the controlling standard, which was the undue burden test adopted in Casey.[19] Two of the justices would have implemented rational basis as the standard of review.[20] Finally, two justices would not have overruled PPH 2018 at all, and thus would have kept in place strict scrutiny review.[21] For four years, nothing happened, there was no appeal nor was there an attempt by the legislature to pass another fetal heartbeat law.[22]

After the United States Supreme Court issued Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 142 S. Ct. 2228, the State moved to dissolve the permanent injunction of the fetal heartbeat law. The district court denied the motion for three reasons: (1) the State’s motion was untimely under Iowa Rules of Civil Procedure 1.1012 and 1.1013, (2) the court did not have the authority to dissolve such an injunction due to a substantial change in the law, and (3) there had not been a substantial change in the law because the relevant standard remained undue burden.[23]

With a convoluted procedural history, an unclear standard of review, and a Court being keenly watched from the front row,[24] many expected the worst when, in April 2023, the Iowa Supreme Court heard the argument for Planned Parenthood v. Reynolds ex. rel. State, No. 22–2036, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68 (Iowa 2023).

III. Discussion

For how highly anticipated the decision was, legally the result was unextraordinary. Socially, however, it represented a massive victory for thousands of Iowans. There was no controlling opinion, but rather because of a 3–3 split, by the operation of law, the lower court’s ruling stood. Abortion remains somewhat protected in Iowa for now.

It is not common for 3–3 cases to have written opinions,[25] however the justices quibbled over whether this case required a written explanation.[26] Nonetheless, the case provided a unique insight into the decision-making for the justices as these opinions were “solely for the purpose of airing individual justices’ views . . . .”[27]

Justice Waterman, joined by Chief Justice Christensen and Justice Mansfield let the district court ruling stand. Their reasoning stood on two principles. The first was that there were discretionary reasons for denying the State’s writ of certiorari and therefore not necessary to reach the merits of the claim.[28] The second principle was that even if the Court granted the writ, the Court could not sustain the writ—and thus overrule the district court—because it did not act illegally or outside its jurisdiction when it determined that the injunction was still valid under the existing law.[29] Justice McDonald, joined by Justices McDermott and May, and Justice McDermott, joined by Justices McDonald and May, would have granted the writ and reached the merits of the claim.[30]

A. The Discretionary Reasons to Deny the Writ

Justice Waterman wrote that there were six discretionary reasons for not granting the writ. The first was that the injunction that was entered in 2019 had never been appealed.[31] Justice McDonald wrote that the parties may not have been subject to the Iowa Rules of Civil Procedure because of the court’s inherent common law authority to hear an appeal when the circumstances require such review.[32] Justice Waterman reasoned it weighed against the petitioners in this case because they were the same parties four years ago which chose not to appeal the injunction and thus able to litigate what the proper standard of review may have been.[33]

The second was that at the time the law was passed, because the undue burden standard was controlling, the legislature was enacting a “hypothetical law.”[34] Essentially, the legislators must have known that this law would be deemed unconstitutional. Justices McDonald and McDermott took great issue with the concept of a “hypothetical law.” They reasoned that since it was passed by both chambers, signed by the Governor, codified, and then even remained codified after it was held unconstitutional, it still remains an actual law.[35]

The third reason was that there is a potential for a constitutional amendment to be placed on the ballot in 2024 which would protect the “right of life”,[36] however, the current Iowa Legislature has not yet taken the second required vote to place the measure on the ballot.[37] Neither Justices McDonald nor McDermott address this point.

The fourth reason is that the current Iowa Legislature has never reenacted the fetal heartbeat law.[38] Justice Waterman reasoned that since the legislature knew that the district court refused to dissolve the permanent injunction before the 2023 legislative session, it could have reenacted the fetal heartbeat bill, then litigated the standard of review when that law would have inevitably been challenged.[39] Justice McDonald points out that just because a law has become unconstitutional, does not mean that it ceases to exist and therefore the legislature did not need to reenact the law.[40] Justice McDonald believes such an argument “curtails the legislative power” and “enlarges the judicial power.”[41] Justice McDermott agrees with this reasoning, but adds separately that it was reasonable for the Iowa Legislature to expect the judiciary to be able to handle this situation, and that he is “embarrassed to think that we might actually fault the legislature for believing that the judiciary could correctly and more efficiently resolve the issue in this appeal.”[42]

The fifth reason is that members of the Iowa Legislature filed an amicus brief “urging [the Court] to reach the merits and adopt rational basis review of the fetal heartbeat bill.”[43] However, the members who signed the brief would not be enough to reenact the law in the Iowa House of Representatives.[44] Justice McDermott states that this is not evidence that the legislature has rejected the law which is still on the books.[45] Justice McDonald does not tackle this point directly but instead states that “[t]he public can review [Justice Waterman’s] reasons and decide, for example, whether it is logical, legal, or legitimate to decide the case on the grounds that not enough nonparties to this case joined an amicus brief.”[46]

The final reason is that Justice Oxley had to recuse herself from this case and such an “incredibly consequential constitutional issue[] relating to abortion should understandably be decided by a full court if at all possible.” Justice McDonald and Justice McDermott do not address this point.

Justice McDonald and McDermott would have granted review in this case. Justice McDonald wrote that since this case presented “pressing questions of constitutional law and civil procedure and meets the criteria for retention and decision by this court,” he would have granted the petition for writ of certiorari.[47] Justice McDonald goes on to cite a series of cases that have decided “issues of far lesser visibility and consequence” where the court did grant the writ.[48] He states that this case presents a constitutional question, a question of public importance, and a question that could change legal principles, thus it satisfies retention criteria and the Court should have granted the writ to reach the merits of the claim.[49]

B. Even if the Court granted the writ, the Justices Were Split on Whether They Would Have Sustained the Writ.

Had the Court granted the writ of certiorari and reached the merits of the claim, Justice Waterman and Justice McDonald differed on whether the State had satisfied the test for sustaining the writ. That test being that the district court acted illegally or outside its jurisdiction.[50]

Justice Waterman agreed with the district court’s third ground for denying the State’s motion.[51] That is, that PPH 2022 left intact the undue burden standard from PPH 2015 and the fetal heartbeat law would not survive the undue burden standard.[52] Justice Waterman points out that after PPH 2022, the case was remanded back to the district court and parties were able to present evidence as to what the appropriate standard should be. Planned Parenthood dropped the claim and thus there was no argument as to the correct standard.[53]

Justices McDonald and McDermott have a different view of the effect of PPH 2022. Justice McDonald points out that the undue burden standard was adopted by PPH 2015 because the State conceded at oral argument that Iowa law on abortion regulation follows federal law.[54] Therefore, when Dobbs overruled both Roe and Casey, that in effect overruled the undue burden standard seen in Iowa law because it was coextensive with the federal doctrine.[55] State Supreme Courts are not required to follow the United States Supreme Court in every instance, including its abortion regulation doctrines. Justice Waterman points out that the Iowa Supreme Court needs to analyze its constitution independently from the United States Supreme Court’s analysis of the United States Constitution.[56] Justice McDonald points out that this belief in independent analysis does not align with personal precedent as Justice Waterman, Chief Justice Christensen, and Justice Mansfield have joined in an opinion before criticizing Justices McDonald and McDermott for taking an independent analysis approach in an unrelated Fourth Amendment analogous case.[57]

IV. Impact

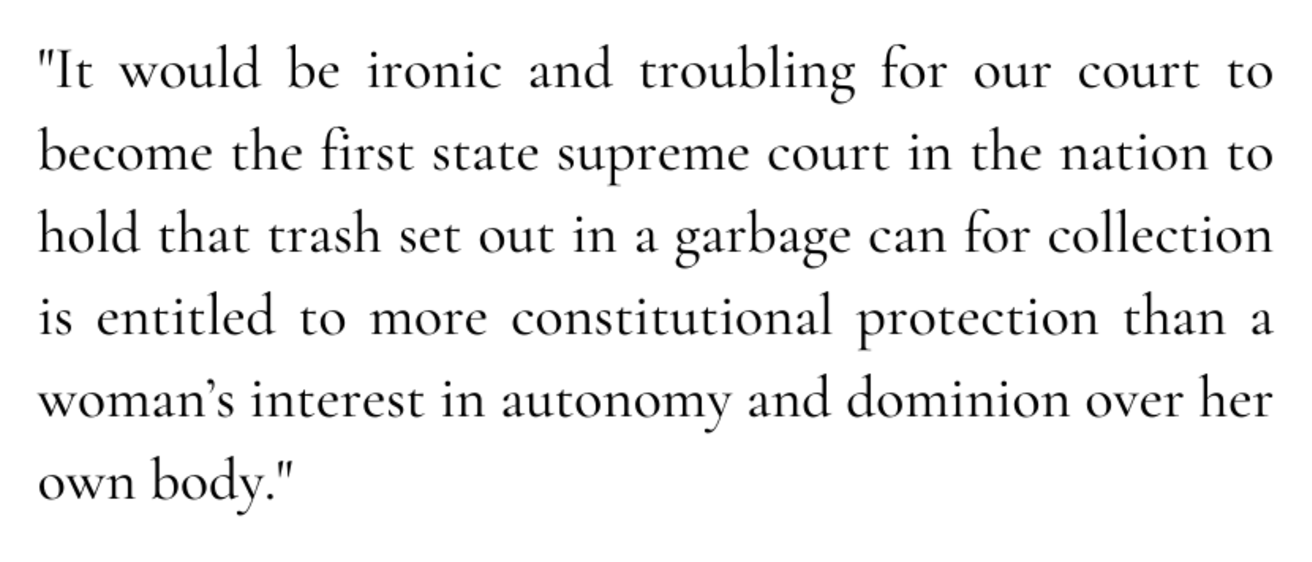

So where is this headed? This is the question that many Iowans are asking. Do these “personal advisory opinions” shed a glimmer of hope for the right to choose in the State of Iowa? It is unclear. Circulating on social media and in news outlets is Justice Waterman’s quote which may show he has swayed from old positions: “It would be ironic and troubling for our court to become the first state supreme court in the nation to hold that trash set out in a garbage can for collection is entitled to more constitutional protection than a woman’s interest in autonomy and dominion over her own body.”

However, it is another phrase that may hint that three justices may believe the Iowa Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause protects the right to an abortion: “PPH [2022] reiterated that ‘being a parent is a life-altering obligation that falls unevenly on women in society.’”[58] Justice McDonald and McDermott state that both PPH 2022 and Dobbs foreclosed the argument that there may be an equal protections issue with abortion regulation.[59] They also point out that this belief is the opposite of what both Justice Waterman and Mansfield wrote in their dissent of the PPH 2018 decision which held that the Iowa Constitution protected the right to abortion.[60]

Even if three justices have adopted this view, the wild card which still remains is Justice Oxley. Justice Oxley had to recuse herself from this case because she once represented the Emma Goldman Clinic, a party to the case.[61] Justice Oxley joined the court in 2020.[62] Since her appointment, Justice Oxley was in the majority opinion in PPH 2022 which stated that the Iowa Constitution did not view abortion as a fundamental right. Justice Oxley wrote the majority opinion in Planned Parenthood of the Heartland, Inc. v. Kim Reynolds, 962 N.W.2d 37 (Iowa 2021) which upheld a statutory amendment that withheld funding from a program that provided abortion services along with other sex education.

Ultimately, it is not clear what would have happened if Justice Oxley did not have to recuse herself. What seems likely in the future however is that the Iowa constitutional standard for abortion regulation will soon be reviewed. Justice Waterman stated that the “procedural issues presented in this case fall away if the legislature enacts a new abortion law.”[63] Justices McDonald, McDermott, and May were explicit––they would review this law under rational basis review and thus hold it constitutional.[64] For today, abortion up to 20 weeks remains legal in Iowa and pregnant individuals will have access to necessary healthcare for the time being. This case and the celebration that followed may be a relic of a pre-Dobbs world and likely one of the final proverbial breaths that abortion access takes in the Hawkeye State.

[1] Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Org., 142 S. Ct. 2228, 2279 (2022).

[2] 142 S. Ct. 2228 (2022).

[3] Caroline Kitchener et al., States Where Abortion is Legal, Banned, or Under Threat, Wash. Post (May 26, 2023 12:18 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/06/24/abortion-state-laws-criminalization-roe [https://perma.cc/UJ4J-FTFF].

[4] Tracking the States Where Abortion is Now Banned, N.Y. Times (June 16, 2023 4:00 PM), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade.html [https://perma.cc/FL8N-D6LK].

[5] See, e.g., Marilou Johanek, Extremist Ohio Legislators Created the Law Forcing Child Rape Victims to Give Birth, Ohio Capital J. (July 19, 2022 3:20 AM), https://ohiocapitaljournal.com/2022/07/19/extremist-ohio-statehouse-legislators-created-the-law-forcing-child-rape-victims-to-give-birth [https://perma.cc/SJE9-BBC9].

[6] Order, Planned Parenthood v. Reynolds ex. rel. State, No. 22–2036, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68, at *5 (Iowa June. 16, 2023) (Waterman, J.)

[7] Id. at *3 (Waterman, J.).

[8] Id. at *41–42 (McDonald, J.).

[9] Id. at *42 (McDonald, J.).

[10] Id.

[11] Id.; Planned Parenthood of the Heartland, Inc. v. Iowa Board of Medicine, 865 N.W.2d 252, 262 (Iowa 2015) (applying the Undue Burden Standard), overruled by Planned Parenthood of the Heartland, Inc. v. Reynolds ex rel. State, 975 N.W.2d 7120, 715 (Iowa 2022).

[12] Order, Planned Parenthood v. Reynolds ex. rel. State, No. 22–2036, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68, at *18 (Iowa June. 16, 2023) (Waterman, J.)

[13] 915 N.W.2d 206, 237 (Iowa 2018).

[14] Id.

[15] Order, Planned Parenthood of the Heartland, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68, at *43 (McDonald, J.).

[16] Id. at *43–44.

[17] Tony Leys & Stephen Gruber-Miller, Iowa Supreme Court Rejects 72-Hour Abortion Waiting Period Requirement, Says Women Have Right to Abortion, Des Moines Register (June 29, 2018 6:14 PM), https://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/news/health/2018/06/29/abortion-iowa-supreme-court-planned-parenthood-72-hour-waiting-period-american-civil-liberties-union/745068002 [https://perma.cc/RMS9-EWV7].

[18] Planned Parenthood of the Heartland, Inc. v. Reynolds ex rel. State, 975 N.W.2d 712, 715 (Iowa 2022).

[19] Order, Planned Parenthood of the Heartland, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68, at *44 (McDonald, J.). Those justices were Justice Waterman, Justice Mansfield, and Justice Oxley. PPH 2022, 975 N.W.2d 710, 713 (Iowa 2022).

[20] Id. Justice McDermott and Justice McDonald were the justices that would have held for rational basis review. PPH 2022, 975 N.W.2d 710, 713 (Iowa 2022).

[21] Id. Chief Justice Christensen and Justice Appel were the justices who would not have overruled PPH 2018. PPH 2022, 975 N.W.2d 710, 713 (Iowa 2022).

[23] Order, Planned Parenthood v. Reynolds ex. rel. State, No. 22–2036, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68, at *4 n. 2 (Iowa June. 16, 2023) (Waterman, J.)

[24] Clark Kauffman, Reynolds Was in Supreme Court’s Secure Office Area Prior to Oral Arguments on Abortion Case, Iowa Capital Dispatch (Apr. 12, 2021 5:51 PM), https://iowacapitaldispatch.com/2023/04/12/reynolds-was-in-supreme-courts-secure-office-area-prior-to-oral-arguments-on-abortion-case [https://perma.cc/GN9G-KQQ2] (“Video of the oral arguments appears to show Reynolds seated in the front row of the gallery facing the justices as they heard arguments in the case.”); Gov. Reynolds, Republican Leadership Respond to Iowa Supreme Court’s Opinion on Fetal Heartbeat Bill Injunction, Office of the Gov. of Iowa Kim Reynolds (June 16, 2023), https://governor.iowa.gov/press-release/2023-06-16/gov-reynolds-republican-leadership-respond-iowa-supreme-courts-opinion [https://perma.cc/FK9C-RMKP] (“To say that today’s lack of action by the Iowa Supreme Court is a disappointment is an understatement.”).

[25] Order, Planned Parenthood of the Heartland, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68, at *7 (Waterman, J.) (“Since [the last opinion in a 3–3 case], over the last [14] years, we have had [18] cases where the court was divided 3–3 on the overall resolution of the case. This meant there was nothing for “the court” to say, and in each of those [18] cases, we filed no opinions.” (citation omitted)).

[26] Id. at *9 (Waterman, J.) (“Our three colleagues insist on writing, so we must explain our views to provide balance.”).

[27] Id. at *7.

[28] Id. at * 9.

[29] Id. at *9–10.

[30] Id. at *71 (McDonald, J.).

[31] Order, Planned Parenthood v. Reynolds ex. rel. State, No. 22–2036, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68, at *12 (Iowa June. 16, 2023) (Waterman, J.)

[32] Id. at *53 (McDonald, J).

[33] See id. at *12–13 (Waterman, J.) (“The State was content to have the fetal heartbeat bill enjoined from taking effect. The same Governor who declined to appeal in 2-19 was reelected and holds that office today.”).

[34] Id. at *13.

[35] Id. at *47 (McDonald, J.).

[36] Stephen Gruber-Miller, Iowa Legislature Approves Anti-Abortion Constitutional Amendment. Legislature Must Pass It Again Before It Goes to Voters., Des Moines Register (May 19, 2021 4:48 PM), https://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/news/politics/2021/05/19/iowa-legislature-house-approves-anti-abortion-constitutional-amendment-senate-supreme-court/5156817001 [https://perma.cc/MF4Z-9XNA].

[37] Order, Planned Parenthood v. Reynolds ex. rel. State, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68, at *13 (Waterman, J.).

[38] Order, Planned Parenthood v. Reynolds ex. rel. State, No. 22–2036, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68, at *14 (Iowa June. 16, 2023) (Waterman, J.).

[39] Id.

[40] Id. at *48 (McDonald, J.).

[41] Id. at *51.

[42] Id. at *79–80 (McDermott, J.).

[43] Id. at *14 (Waterman, J.).

[44] Order, Planned Parenthood v. Reynolds ex. rel. State, No. 22–2036, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68, at *14–15 (Iowa June. 16, 2023) (Waterman, J.).

[45] Id. at *78 (McDermott, J.).

[46] Id. at *73 (McDonald, J.).

[47] Id. at *71.

[48] Id.

[49] Id.

[50] Order, Planned Parenthood v. Reynolds ex. rel. State, No. 22–2036, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68, at *9–10 (Iowa June. 16, 2023) (Waterman, J.).

[51] Id. at *16–17.

[52] Id. at *17.

[53] Id. at *18.

[54] Id. at *59–60 (McDonald, J.).

[55] Id. at *40–41.

[56] Order, Planned Parenthood v. Reynolds ex. rel. State, No. 22–2036, 2023 Iowa Sup. LEXIS 68, at *26 (Iowa June. 16, 2023) (Waterman, J.).

[57] Id. at *64 (McDonald, J.).

[58] Id. at *28 (Waterman, J.) (quoting PPH 2022, 975 N.W.2d at 746).

[59] Id. at *67 (McDonald, J.).

[60] Id. at *68–69.

[61] Adam Edelman, Six-week Abortion Ban Blocked by Iowa Supreme Court, NBC News (June 16, 2023 9:13 AM), https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/six-week-abortion-ban-blocked-iowa-supreme-court-rcna89620 [https://perma.cc/Q84U-CJAL].

[62] Dana Oxley, Iowa Judicial Branch, https://www.iowacourts.gov/iowa-courts/supreme-court/justices/dana-oxley [https://perma.cc/C569-QK55].

[63] 12 (Waterman).

[64] 51 (McDonald) (“I did, and still do, believe this court has a duty to independently interpret the Iowa Constitution, which is why I cite Wright above and why I joined Justice McDermott’s opinion in PPH 2022 applying rational basis review prior to Dobbs being filed.”); 60 (McDermott) (“I join in full Justice McDonald’s opinion today, which spells out why we should grant the State’s writ of certiorari and apply the rational basis test.”).